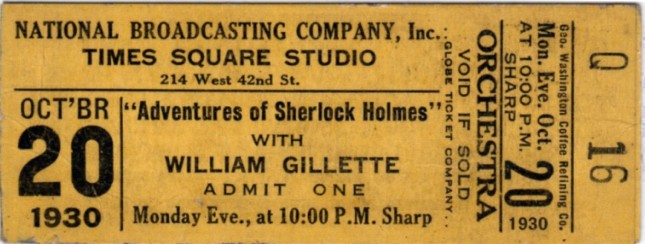

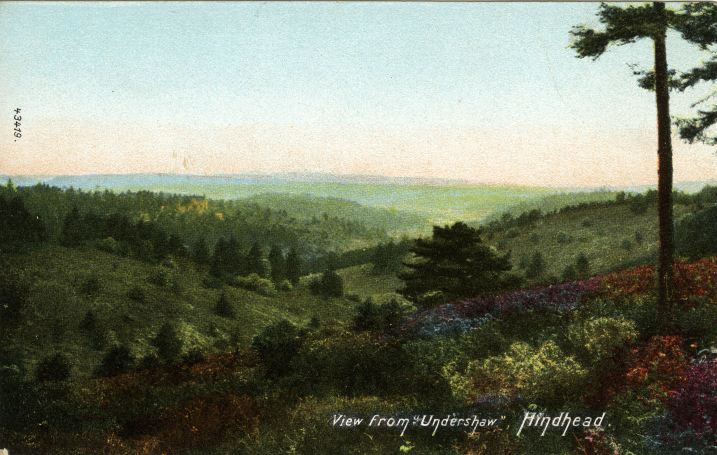

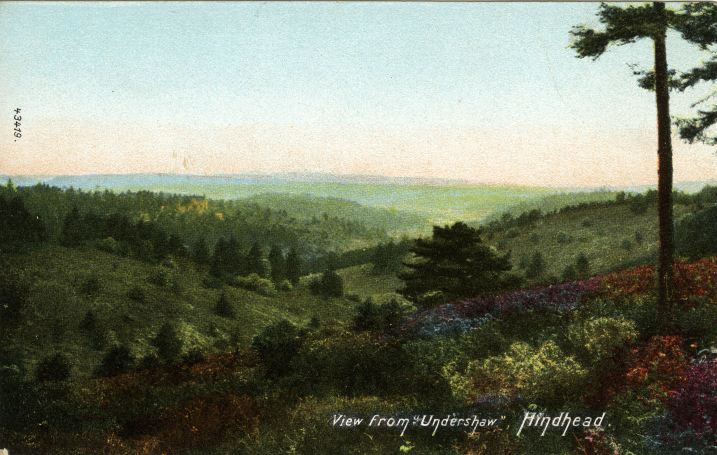

Undershaw looking South to Nutcomb Valley

My first book! That was written when I was six years of age! But if I am to tell you about myself, I suppose I had better begin at the beginning.”

The speaker was lying on a chintz covered sofa in the pretty drawing-room of his house at Hindhead, down in Surrey. The forenoon sun was streaming in through one of the mullioned windows, of which the bars were softened by the delicate fringe of green of the creepers which spread all along them. The whole room was full of soft light, which showed the fine old furniture and the multitude of dainty knick-knacks to perfection. Even the many quaint and pretty pictures seemed to stand out from the walls.

From where I sat the whole of the lovely valley, at the very head of which the house stands, lay before me. Due south it falls away, spreading wider as it goes, till its lines are lost in distance, an endless sea of greenery. Far away there are ranges of hills piling up, one behind the other, in undulations of varying blue. Even the whole sweep of the horizon visible from our altitude is like a wavy sea. Nearer at hand the wonderful green of the valley is articulated by the minor curves and slopes, the trend of surrounding hills. The mighty carpet of green is of the fresh young bracken, whose shoots seem close and are like little croziers wrought in emerald. Against this the rising pine trees seem like dark masses. Close to us, beyond the vivid patch of tennis lawn, are some masses of color which are simply gorgeous amid the expanse of green. Great shrubs of yellow bloom, clumps of purple rhododendron, luxuriant alder, with masses of snowy flowers starred in their own peculiar green. An expanse which, whether seen from near or far, in unity or detail, simply ravishes the eye with its myriad beauties.

We had motored up the previous afternoon from Guildford, some twelve miles distant. The last seven miles of the journey up the steep, winding road shows one of the loveliest scenes in England—a scene that brings at every new phase fresh memories of Turner. Indeed, Turner himself loved this piece of the old Portsmouth road. Is not one of the weirdest pictures of the Liber Studiorum, “Gallows Hill,” taken from it? But here was the crown of it all—that wide expanse seen beyond this foreground of idyllic beauty.

UNDERSHAW HOME AT HINDHEAD.

Conan Doyle built his home Undershaw in the western angle at the joining of the road from Haslemere with the Portsmouth road, just below the very top of the hill. It stands on a little platform lying below the road. As north and east of it is a thick grove of trees and shrubs, it is completely sheltered from stranger eyes except from down the valley. It is so sheltered from cold winds that the architect felt justified in having lots of windows, so that the whole place is full of light. Nevertheless, it is cozy and snug to a remarkable degree, and has everywhere that sense of “home” which is so delightful to occupant and stranger alike. Throughout it is full of interesting things got together for their interesting association with the author’s life and adventures, for their prettiness, or as curios, or works of art.

The owner of this almost fairy pleasure house is a big man, massive and burly, and of great strength. His head and face are broad and strong. His eyes are blue with a peculiar effect in light, for they seem to have two shades of blue in the iris. His voice is strong and resonant—a very masculine voice.

The “interview” which followed was the result of many questions. The subject of it was most kind and amenable, thoroughly understanding everything and willing to enlighten me as I required. But he is not naturally a pushing man or an egotist, and it was necessary to keep him resolutely to the point of his own identity. I say this as his various statements were so lucid and illuminative that I think it better to give them in his own words in the sequence of a direct narrative. After all, there is nothing like a man’s ipsissima verba to show the reality of the individual through the mistiness of words. I omit questions except where necessary, and only venture to add comment or description where such may add to the reader’s enlightenment.

DOYLE’S IMAGINATIVE FORBEARS.

“My people on the father’s side,” said the creator of “Sherlock Holmes,” “we all artists of a peculiarly imaginative type. My father, Charles Doyle, was in truth a great unrecognised genius. He drifted to Edinburgh from London in his early youth, and so he lost the chance of living before the public eye. His wild and strange fancies alarmed, I think, rather than pleased the stolid Scotchmen of the 50’s and 60’s. His mind ran on strange moonlight effects, done with extraordinary skill in water colors; dancing witches, drowning seamen, death coaches on lonely moors at night and goblins chasing children across churchyards.”

All these pictures were in the room, or in some of those adjacent. With them were a host of others, delicate fancies and weird flights of imagination. There was one tiny picture of a little fairy carrying a branch and leading a beetle by a string, which was daintily sweet.

“I have myself no turn for this form of art at all beyond a very keen color sense which makes a discord of shades perfectly painful to my eye. I suppose, however, that there is a metabolism in these things, and that any sense I have for dramatic effect corresponds, or is an equivalent, in some degree, to the artistic nature of my father, whom, by the way, I in no degree resemble physically. But my real love for letters, my instinct for story-telling, springs, I believe, from my mother, who is on Anglo-Celtic stock, with the glamour and romance of the Celt very strongly marked. Her I do resemble physically, and also in character, so that I take my leanings towards romance rather from her side than my father’s. In my early childhood, as far back as I can remember anything at all, the vivid stories which she would tell me stand out so clearly that they obscure the real facts of my life. It is not only that she was—is still—a wonderful story-teller, but she had, I remember, an art of sinking her voice to a horror-stricken whisper when she came to a crisis in her narrative, which makes me goose-fleshy now when I think of it. I am sure, looking back, that it was in attempting to emulate these stories of my childhood that I first began weaving dreams myself.

A SIX-YEAR-OLD AUTHOR.

“When I was six I wrote a book of adventure—doubtless my mother has it still. I illustrated it myself. It must be an absurd production, but still it showed the set of my mind. When I went to school I carried the characteristic with me. There I was in some demand as a story-teller. I could start a hero off from home and carry him through an interminable succession of wayside happenings which would, if necessary, last through the spare hours of a whole term. This faculty remained with me all my school days, and the only scholastic success I can ever remember lay in the direction of English essays and poetry. I was no good at either classics or mathematics; even my English I wrote as pleasure, not as work.

AT SCHOOL IN GERMANY.

“After leaving Stonyhurst I was sent to a ‘finishing’ school in Germany, the Tyrol. There again my tendency to letters asserted itself. I started and edited a school magazine. Although the German acquired was indifferent, I think I had great benefit from the small but select English library. Macaulay and Scott, I remember, were my favourite authors. But I was and am still an omnivorous reader, with very catholic sympathies. There is hardly anything which does not interest me. I have sometimes tested myself by going into a large library and noting which of the books I am tempted to take down. I think that if let loose in such a place on a wet day my first choice would be military memoirs; but I am deeply interested also in criminology, in all sides of history, in science—so far as I can follow it—in comparative theology—if it is not ruined by the heavy touch of the writer—in travel—if the author has the skill to keep a glamour over his picture—in any form of fiction. Indeed, it would be difficult to name any form of true literature which does not give me intense pleasure.

STUDYING MEDICINE IN AULD EDINBORO.

“In 1876 I drifted into the study of medicine. The reason largely was that my people lived in Edinburgh”—he pronounces the word in Scotch fashion, “Edinboro”—”and there is a famous medical school there. For four years I went through the curriculum. My people were not at that time wealthy, and it was a struggle to keep me at college. So I compressed my classes into the winter, and devoted each summer to serving as a medical assistant, and so earning a little money to help to pay the fees. I served in this way in Sheffield, in the country districts in Shropshire, and finally in Birmingham —a billet to which I returned three times. The practice lay mostly in the slums of that great city, and I certainly saw a large variety of character and of life, such as I could hardly have known so intimately in any other way.

“The one trouble to me in this arrangement of my life was that I had no means of gratifying the love of athletics which was very strong within me. I used to box a good deal, for that consumed little time; but my cricket and football were neglected. I can say, however, that I have played for my university in both cricket and Rugby football. I had then no time or chance of being a constant player; I feel justified, therefore, in taking it out at the other end. I played a heavy match at football when I was forty-two years of age, and I still, at the age of forty-eight, play cricket twice a week. So I claim now the debts which were not paid me in my youth.

SURGEON TO AN ARCTIC WHALER.

“When I was nearly twenty-one a friend of mine who had been surgeon to a whaler in the Arctic seas told me that he was unable to return that summer, and offered me the billet. I was away for seven months in the Greenland ocean. I came of age in 80 degrees north latitude.

“This was a delightful period of my life. There are eight boats to a whaler, and the eighth, which is kept as a sort of emergency boat, is manned by the so-called ‘idlers’ of the ship. These consisted, in this case, of myself, the steward, the second engineer and an old seaman. But it happened that, with the exception of the veteran, we were all young and keen; and I think our boat was as good as any.”

As he spoke he could not fail to remember the harpoons hanging on the staircase wall. They seemed to account for this enthusiasm. He went on:

“One of the truest compliments I ever had paid me in my life was when the captain offered to make me the harpooner as well as surgeon if I would come for another year. When you think that a whale was then worth some £2,000 and that hit or miss depends on the nerve of the harpooner, I am proud to think that the skipper, old John Grey, should have offered me such a post.

“On returning home from the Arctic I took my degree, having been thrown back one year by the fact of going North. I was twenty-two when I qualified, and, thanks to my numerous assistantships, had a very varied experience behind me.

DOWN THE WEST AFRICAN COAST.

“Almost immediately afterward I was offered the post of surgeon to a steamer going down the west coast of Africa. I was again most fortunate in my captain, and the voyage was a delightful one. We were away four months and the pleasure of my experience was only marred by my getting the rather virulent fever which prevails on that coast. Two of us got it, and the other man died, so that I suppose I may call myself lucky.

“On my return to England I settled in practice, first in Plymouth and then, after a few months, at Southsea, the fashionable suburb of Portsmouth. My adventures in that rather romantic period, and all my mental and spiritual aspirations, are written down in ‘The Stark Munro Letters’, a book which, with the exception of one chapter, is a very close autobiography.

“In this period my literary tendencies had slowly developed. During the years of my studentship my life was so full of work that, though I read a great deal, I had little time to cultivate writing. After starting in practice, however, I had much—too much—time on my hands; and then I began to write voluminously.

“Most of it was, I think, pretty poor stuff; but it was apprentice work, and I always hoped that with practice I might learn to use my tools.

“FINDING HIMSELF” IN LITERATURE.

“Every writer is imitative at first. I think that is an absolute rule; though sometimes he throws back on some model which is not easily traced. My early work, as I look back on it, was a sort of debased composite photograph in which five or six different styles were contending for the mastery. Stevenson was a strong influence; so was Bret Harte; so was Dickens; so were several others.

“Eventually, however, a man ‘finds himself,’ or rather perhaps it is that he grows more deft in concealing the influences which blend with one another until they form what means a new and constant style.

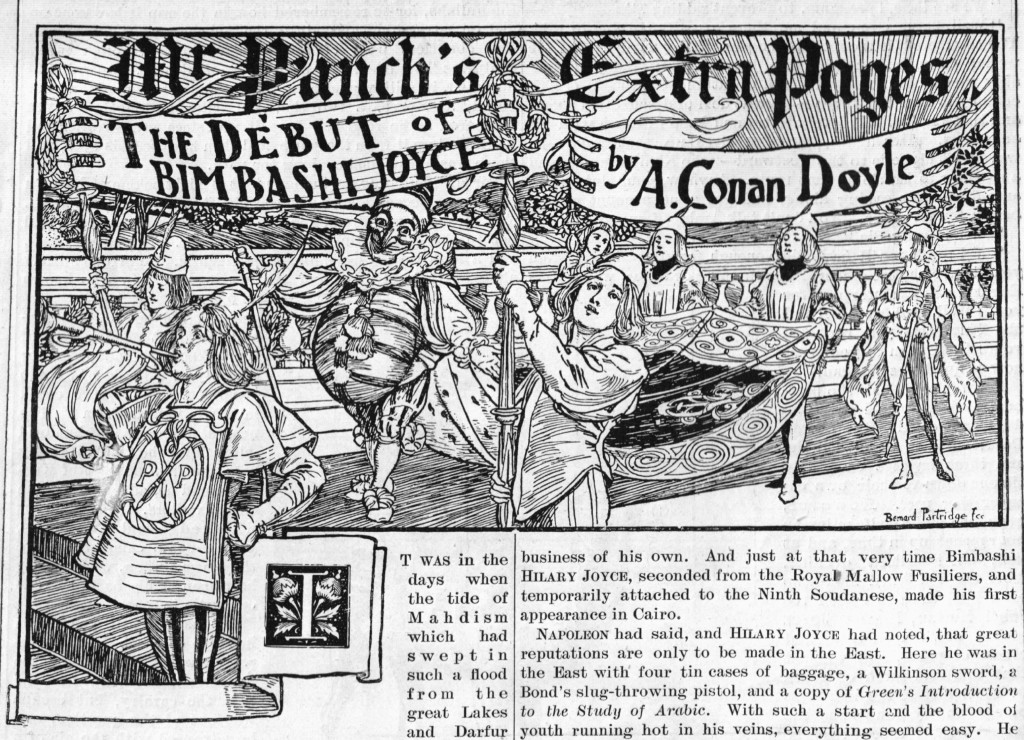

“I suppose that during those early years I wrote not less than fifty short stories. The first appeared in 1878 while I was still a student. It was in Chambers’s Journal and was called ‘The Mystery of the Sassassa Valley’. I had three guineas for it. After receiving that little check I was like a beast that has once tasted blood, for I knew that whatever rebuffs I might receive—and God knows I had plenty—I had once proved I could earn gold, and the spirit was in me to do it again. It was a delightful opportunity for carrying into actuality the dreams of my youth. I had to earn money by some form of work, and that was the sort of work I longed to do.

TEN YEARS OF ANONYMITY

“For ten years I wrote short stories; roughly, from 1877 to 1887. During that time I do not think I ever earned £50 in any year by my pen, though I worked incessantly. Nearly all the magazines published the stories anonymously—a most iniquitous fashion by which all chance of promotion is barred to young writers. The best of these stories have since been published in the volume called The Captain of the Pole Star! Sometimes I saw my stories praised by critics, but the criticism never came to my address. The Cornhill Magazine, Temple Bar and London Society were the chief magazines in which my stories appeared.

“Finally in 1887 I wrote A Study in Scarlet, the first book which introduced Sherlock Holmes. I don’t know how I got that name. I was looking the other day at a bit of paper on which I had scribbled ‘Sherringford Holmes’ and ‘Sherrington Hope’ and all sorts of other combinations. Finally at the bottom of the paper I had written ‘Sherlock Holmes’. ‘A Study in Scarlet’ appeared in a Christmas number of Beeton’s Annual. The book had no particular success at the time, though many people have been good enough to read it since.

“MICAH CLARKE” AND “THE WHITE COMPANY”.

“My next book was ‘Micah Clarke,’ a historical novel. This met with a good reception from the critics and the public; and from that time onward I had no further difficulty in disposing of my manuscripts. When two years later I wrote ‘The White Company’ I felt that my position was strong enough to enable me to give up practice. I still clung to my profession, for I came to London and started as an oculist. After six months, however, this also seemed unnecessary, and I finally retired. I have not indulged in my profession since, except when I went campaigning.”

That he did good service in that noble profession in the South African war is attested not only by his book on the record of the Langman Hospital, but by a noble silver bowl which stands at a corner of his house in Hind-head, on which is inscribed:

“To Arthur Conan Doyle, who at a great crisis—in word and deed— served his country.”

When he had come to the part in his history where he had started his bark on the sea of literature, I think he considered that his duty with regard to the interview. In obedience to my request, however, he went on. I wished that the American people might hear some special comment on their own affairs:

DOYLE’S AMERICAN TOUR

“In 1894 I went on a lecturing tour to America. I had no hopes of any success in the matter; my idea was simply to see a country in which I took a deep interest, and to pay my expenses while I was so doing. Major Pond, however, in his enthusiastic way fixed up a considerable programme for me, so that I was forced to do rather more than to pay my expenses and rather less in the way of seeing the country. I was there, all told, between four and five months, and the fact that I was lecturing had the one advantage that it took me into some of the byways and smaller towns that I should not have otherwise visited.

“I came away from America with a deep admiration for both the country and the people; and much touched by all the kindness and even affection which I had encountered. It has left a lasting impression on my mind which the lapse of thirteen years has in no way effaced. I want to go again without having any work to do, and I want to go out West and Southwest. One feels that society with its highly organised life is to some degree the same everywhere throughout the world, but that the real distinctive America is that portion which is still finding itself, as it were, and has not yet set into its final form.

“I read Wells’s book on the subject the other day; it seemed to me to be very deep and very suggestive. I should think that Americans need not mind frank criticism from such a man as he, for his own mind is essentially democratic and American.

“But the fact is that these various dangers and drawbacks which one sees—the dangers of the great trusts—the dangers of violent labor unions— the dangers of the multi-millionaire—the dangers of individual character and violence becoming too strong for the organised legal machinery of the community—all these things are probably prominent problems to be solved by the human race, and only showing up in America because things move faster there and are on a large scale. But always behind the turmoil are ranked the millions of steady, solid, law-supporting citizens; and one knows that in the end all will be well.

“As I am speaking of America I remember one incident that comes back vividly to my mind. When I was there a strong wave of anti-British feeling was passing over the country. It was not shown offensively to the stranger within their gates, but one could hardly pick up any sort of newspaper without reading what was painful and usually untrue about one’s country. On one occasion at Detroit this feeling showed on the surface. A small supper was given to me by some kind and hospitable friends at a club there. We looked upon the wine when it was red, and at a late stage of the evening, politics having come up, one of the company made a speech in which he made a severe attack upon Great Britain. I asked my friend Robert Barr, who was in the chair, to allow me to answer the attack. This I did, speaking my mind out of the fulness of my heart. I think no one who was present could fail to have been surprised at the way in which after events bore out my remarks. What I said practically was:

“’You Americans have lived, up to now, within a ring fence of your own. Your country has become so vast, and you have so much to do in peopling it and opening it out, that you have never had to think seriously of outside international politics, and you have lived to some extent in a world of prejudice and of dreams. This period is now drawing swiftly to an end. Your country is filling up, and soon you will have surplus energies which will lead you on into world politics and bring you into closer actual relationships with the other powers. Then your friendships and your enmities will be guided, not by prejudice nor by hereditary dislikes, but by actual practical issues. When that days comes—and it is coming soon—you will find that the only people who will understand you—who will see what your aims are and who will heartily sympathise with you in them, are your own people, the men from whom you are sprung. In a great world-crisis you will find that you have no natural friend among the nations save your own kin; and to the last they will always be at your side!’

“Well, within three years came the Spanish war—the suggested European coalition against America—the strong attitude of Great Britain upon the subject. It was as good an illustration as one could desire of the prediction which I had made in my speech.

“We know very well on this side that if the case were reversed and we ourselves had to look for sympathy and understanding, all minor contentions would vanish in an instant and we should find a strong and true friend by our side.”

A HAPPY ANNOUNCEMENT

One little personal piece of information was given by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle which may make a fitting conclusion to this interview. It was the news of his approaching marriage. Sir Arthur is engaged to a young lady, Miss Jean Leckie of Crowborough, to whom he is to be married in September. His face lit up as he finished: “I am the most lucky of men. May I be worthy of my good fortune!”

The World (New York) 1907